1.28.20

Alec Soth,

Please forgive the audacity of this letter. I reach out in great admiration and respect.

For years, I have relied on photography for reference material, given my incarceration, and have developed a great admiration for the genre. By sheer impulse, I am reaching out to local artists I admire in the hope to ignite a professional dialogue. I have no real expectation but to connect with other artists. Incarceration comes with a low glass ceiling. By no way am I absolved of my past – but I seek to pay something forward through my art and writing…

I pray to you all the duende to continue to inspire through your work…

Much Respect,

Fausto

━

2.5.20

Dear C. Fausto (or should I call you Chris?),

I’m just home from a road trip and found your recent letter awaiting me. You wrote that for years you’d used photography as reference material. I’m wondering if you could tell me more about that. Are there specific photographs you remember using? Are you able to keep printed photos in your cell? If so, what are they, and where do you keep them?

I’m particularly fascinated by the relationship of photography to the lack of freedom. Just today, I received a book in the mail by Libuše Jarcovjáková, a woman who photographed in Communist Prague in the 1970s. She writes:

Faraway places, trips, adventures… that was what really appealed to me. But the Czechoslovakia of my childhood was a country bordered by barbed wire and you weren’t allowed to travel. It was a time of oppression, during which for more than 40 years we were the political vessels of a large Eastern empire. Everything was ideology, you were surrounded by political propaganda from morning to evening… Luckily, I didn’t really take in my surroundings. There was a world of books and pictures and I spent hours imbibing them.

I’m wondering if there are any photographs you are particularly hungry to see. These could be photographs for your writing, or just for personal comfort. They could be of loved ones or faraway places. Is there a place you dream of traveling?

With gratitude,

Alec

━

2.12.20

Hey Alec,

Please allow me to give a little context to my perspective: I spent the bulk of my sentence at Stillwater working in the art department, which is the only full-time vocational studio space in the Department of Corrections [DOC]. I developed as an artist and was granted the privilege of shaping the program and managing 17-20 students with the bulk of the instructing. I wrote a curriculum that mirrored my development done mostly by independent study and experience. Our resources were limited, but looking back, relatively speaking, we were blessed with a lot of opportunities and options to order books, DVDs, and source material. Building a respectable library and materials inventory was one of my great honors. But three years ago, I was transferred to this wasteland of a prison in Rush City. My materials are reduced to a tiny personal inventory that is constantly challenged. My source material is limited to ten books and files that must fit into a 2-foot locker with all my other property. I can only have a limited number of photographs and clippings from magazines. Early on, I gravitated toward portraits, namely of women. I got incarcerated at 22, so I chased that look of allure seen in the eyes of most models, actresses, and musicians. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I just wanted to be seen.

When I was in High School, I played AAU basketball in the summer and went to Washington, D.C., for a tournament. My buddies’ father told us not to waste any film on sites or monuments. He said, “pictures without people are pointless.” After we returned and I had my film developed, I reflected and found that every picture taken without my friends amounted to a bad postcard. That principle always stuck with me until I started to study landscapes. It took me years to appreciate the power of a well-crafted scene. It dawned on me one day that photos without people captured the solitude of a single viewer; that there is always someone ‘in’ the picture. Around that same time, I started to appreciate the artistic vision of the photographer.

In Stillwater, I made collages of clippings and photographs. For years I compiled art, portraits, objects, landscapes, anything that even vaguely caught my attention. I’d collect files of the random ‘inspirations’ that I’d eventually cut out and fit into a puzzle of a sort — matching them only by contour to fit as many as possible on each page in a 3-ring binder. I read somewhere that creativity boils down to the ability to find the connecting threads of contradicting or otherwise separate ideas or things. Whenever I felt stuck or bored, I’d page through these volumes of binders for inspiration while letting my mind wander.

There is this fascinating duality in the concept of escapism in photography. The ability to capture the spirit of a place so fully it serves as a portal. It’s so easy to romanticize it, especially when you’re living a life filled with longing. In the quote you sent, it appears the woman used the materials to endure the limitations, to remind her of a broader perspective.

There’s a quote by Marilynne Robinson from Housekeeping that says, “When do our senses know anything so utterly as when we lack it?” The Czechoslovakian photographer’s childhood is defined by these “faraway places” that come alive in her longing. It is where the value of those photo-graphs comes from, right? I mean, I’m positive whoever lived in those faraway places couldn’t possibly view those landscapes in the same light. It’s that interesting duality — in our desire to escape, we turn toward what we most desire to escape in order to sharpen the vision of what we long for. This wakes us up to the artist within that must confront our fears by quantifying them somehow.

I know it’s pretty early and there is so much to ask. I’m really curious about your journey as an artist. I also know we share a plight with “the darkness of depression” (hope that’s not presumptuous).

Oh, you can call me Chris or Fausto. I publish under C. Fausto, but everyone knows me around here as Chris.

I’ve acknowledged that moving forward I’ll most likely go by Fausto.

Talk to you soon,

Fausto Cabrera

━

3.10.20

Dear Fausto,

I was saddened to hear about all of your restrictions at Rush City. Your predicament makes for a fascinating question: if I were only to have a 2ft locker in which to store all of my property, what would I put in there? I’m reminded of an event I did a few years ago in London in which I was asked to talk about the eight photographs I would take with me to a desert island. Of course, if this were really to be the case, I’m sure I would take pictures of loved ones. I would also want at least one picture of a woman (even at age 50, much less 22.) One of the images I chose was by a Dutch photographer named Ed Van der Elsken. It’s of a beautiful woman with her leg in a cast. She stares out the window at snowy mountains while only wearing underwear. It’s called “Apres Ski.”

I’m always drawn to photographs with windows. For me, they speak to the quality of longing that drew me to photography in the first place. In this case, the longing of the woman to be skiing and the longing of the photographer to be in bed with the woman. Did you ever get the chance to see Hitchcock’s movie Rear Window? Jimmie Stewart stars as a wheelchair-bound photographer who spies on his neighbors — including a sexy dancer and another woman he calls “Miss Lonelyhearts.” I’ve always identified with his character.

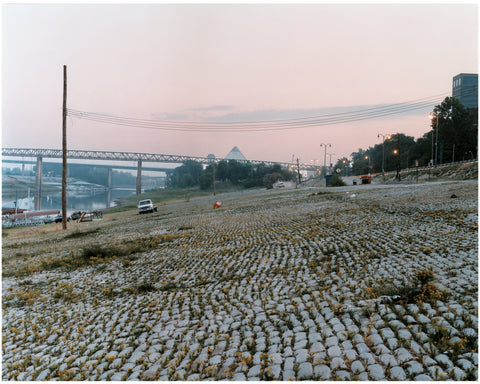

I so appreciated what you said about photographs without people. One of my eight desert island pictures was taken by photographer Robert Frank as part of his book The Americans. It is titled “View from Hotel Window. Butte, Montana. 1955.” It’s an ordinary snapshot without any people. It isn’t even very descriptive of Butte. This picture is less about the view than it is about Robert Frank. You can feel him standing at the window.

I had the chance to look out this very window some years ago while traveling cross country on a project called Broken Manual. This project started as a commission to photograph in the South. When I was in Atlanta, I remembered the story of Eric Rudolph, aka The Olympic Bomber — he was the guy that bombed the 1996 Olympics. He was identified as a suspect in 1998 but wasn’t captured until 2003. The FBI had him on their 10 Most Wanted list and knew he was in the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina, but he was a savvy enough survivalist to escape capture. I was fascinated by his years as a fugitive. So I drove to the location in North Carolina where the FBI eventually found him dumpster-diving.

On my way to that location, I happened to drive by a small Greek Orthodox monastery in Northern Georgia. I ended up photographing one of the few monks living there. He was a relatively young guy who’d been living at the monastery for years. In my mind I made a connection between him and the fugitive. While the reasons these two men left society couldn’t be more different, they both sparked in me a similar longing to escape. Needless to say, yes, I do indeed battle with “the darkness of depression.”

There’s something from your last letter that I wrote down in my journal: “creativity boils down to the ability to find the connecting threads of contradicting or otherwise separate ideas or things.” This is precisely the way it is for me: diving deep into myself and making subconscious connections. I do all sorts of research first, but it’s when it settles, often in the liminal state between wakefulness and sleep, where the threads come together. It feels like magic.

I wonder if you could do something for me. Can you describe the eight photographs you might take to a desert island? These can be loved ones, magazine pictures, anything. The more detail the better.

With gratitude,

Alec

From 'The Parameters of Our Cage' by C. Fausto Cabrera & Alec Soth, published October 2020.